A RECENTLY launched group has set out to commission a piece of art to commemorate the building of the Dalry Bypass.

Named Bypass Art, a sub group of Dalry Community Development Hub, and their aim is to site a piece of public art on the new Dalry Bypass, providing a landmark for the town of Dalry and the Garnock valley.

A landmark on the Dalry Bypass, something that will be seen by thousands of people everyday, will provide them with a unique opportunity to promote the town, and the beautiful countryside surrounding it, a monumental signpost inviting tourists and indeed our own community to explore Dalry and it’s heritage. Incidentally Bypass Art and other members of Dalry Community Development Hub are also working on a project that will create a Heritage Trail within the town!

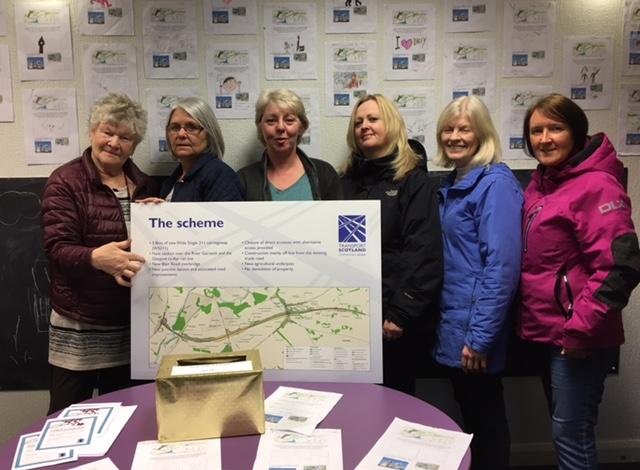

A spokesperson for the group said: “We asked the children from the two local primary schools, St Palladius and Dalry Primary School for their ideas and we held an exhibition displaying their artwork in Dalry Library.

“We also placed a suggestion box in the library and you can look us up on our Facebook page Bypass Art@dalrybypass and share your ideas.

“Thank you to all the pupils from both schools for all the super pictures, and to everyone who took the time to place suggestions in our box.

“We have had thistles, birds, trees, churches and many more, but the most popular suggestion so far has been Bessie Dunlop the Dalry witch.

“We look forward to your support with this unique project.”

THE TALE OF BESSIE DUNLOP

Everyone is familiar with the popular image of the Halloween or Pantomime witch and although she is still often used to scare children, she has also become something of a cartoon figure.

Yet what lies behind this caricature is in fact one of the grimmest episodes in European history: the burning of witches on a massive scale, a mania that raged across Europe for well over two centuries, affecting both catholic and protestant countries, and which condemned hundreds of thousands of innocent people, mainly women, to a horrific death, often for no greater crime than being unusual in behaviour or appearance or simply looking at someone the wrong way.

This witch hysteria, driven by religious fear of the devil in our midst and a zealous hunt for scapegoats, arrived comparatively late in Scotland, but ‘one of the earliest and one of the most extraordinary cases on record,’ was that of Bessie Dunlop the so-called ‘witch of Dalry’.

Bessie’s ‘confession’ is recorded in great detail in Robert Pitcairn’s ‘Criminal Trials’ (1829), drawn from the records of the High Court of Justiciary, and also in Walter Scott’s Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft (1831).

As Scott says ‘her own confession is the principal evidence against her.’

Actually it was the only evidence against her, and would have been extracted or concocted via horrendous torture by sadistic interrogators.

Bessie was in many respects just an ordinary wife and mother who lived with her husband Andra Jack of Lynn in the parish of Dalry.

But what made her different was that she was also a skeelywife or wise woman, skilled in healing and curing humans and animals using traditional folk medicine which sometimes involved ancient charms and superstitions.

Yet in her ‘confession’ she claimed not to have any ‘magical’ powers herself, but to have attained them from her ‘familiar spirit’, one Thom Reid who had been killed at the Battle of Pinkie in 1547 and formerly Baron officer to the Laird of Blair.

Allegedly he first helped Bessie when her own husband and children were sick and gave her herbs and potions to cure them.

She then applied these cures to her neighbours but in reality she was almost certainly highly skilled and highly valued in her community as a midwife and healer and didn’t need any ‘familiar spirit’ to teach her.

Bessie first aroused suspicion, as when she ran into serious trouble with an Irvine burgess over the matter of a stolen cloak and ended up in Irvine Tolbooth.

But worse was soon to follow when she seems to have stumbled into a dangerous case involving the local Sheriff Officer, Jamie Dowgall, and two local blacksmiths, George and Johne Blak, concerning stolen plough-irons, a case that unearthed a tangled and sticky web of intrigue, graft and corruption.

Fingers were soon pointed and clearly a number of important people weren’t now lacking in motivation to accuse her of witchcraft.

When she appeared before the High Court of Justiciary in Edinburgh the assize of 15 important local men, including one Andrew Crawford of ‘Baithlem’ (probably Baidland) the spokesmen of the jury, unanimously found her guilty and she was ‘convict and burnt.’

As was the norm, the only evidence submitted was Bessie’s “confession”, so that she was condemned by her “own” words, produced of course by the ordeals of interrogation and torture.

Bessie’was essentially a ‘victim’ of her own skill in helping and curing people, perhaps a victim of her own innocence, even naivety, and above all, a victim of malicious and misogynistic men.

John Hodgart

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article