Today marks exactly 80 years since the calm, sunny Saturday of March 27, 1943 which saw the biggest loss of life of any single incident in Ayrshire during wartime.

Ardrossan, with its bustling naval harbour, known as HMS Fortitude, and the adjacent oil refinery had been spared the attention of the Luftwaffe, but on that fateful day, it was not enemy action that was to cause a large death toll and subsequent cover up, but something altogether more tragic.

Observers on the North Shore heard the sound of an explosion and noted a dark cloud of smoke at sea about halfway between Ardrossan and Arran.

Unknown to them at the time, the escort aircraft carrier HMS Dasher had exploded, and within eight minutes she had sunk beneath the waves.

Of her crew of 528, 379 young men lost their lives.

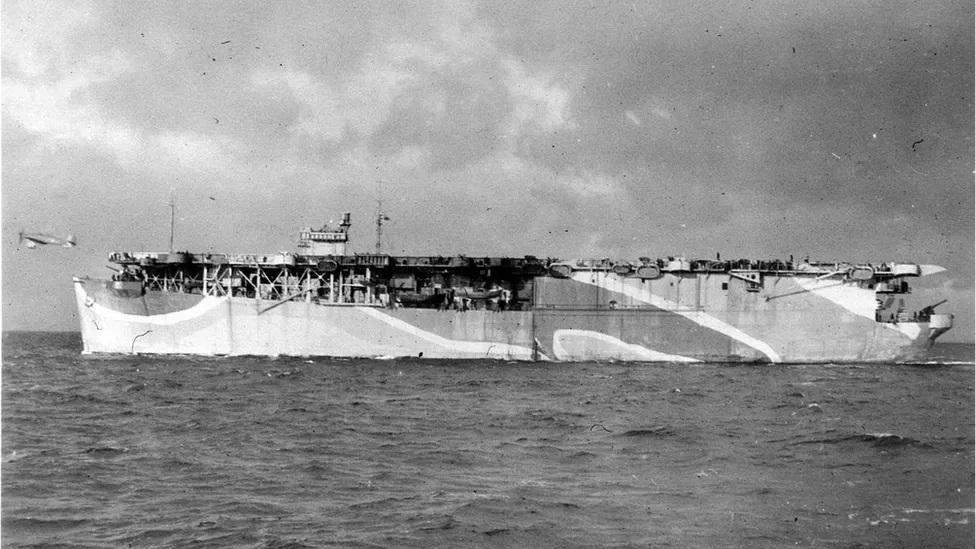

HMS Dasher was one of a series of Avenger-class escort carriers which were merchant ships converted to ships of war.

Originally named Rio de Janeiro, she was launched by the Sun Shipbuilding Company of Chester, Pennsylvania on April 11, 1940, subsequently converted and commissioned into the Royal Navy as HMS Dasher on July 2, 1942.

Dasher had an overall length of 492 feet (150 metres) and was propelled by four diesel engines driving a single shaft. Her job was to escort and protect the convoys vital to Britain’s survival.

Shortly after leaving with a convoy, Dasher suffered engine trouble and turned back to the Firth of Clyde.

After repairs were carried out, six Swordfish torpedo bombers and six Sea Hurricanes fighters of 891 Squadron joined Dasher and commenced landing and take-off exercises.

And so it was on that fateful Saturday, March 27, 1943, that the off-duty watch relaxed and those on watch went about their duties until 4.40pm when there was an enormous explosion – such that the two ton aircraft lift was flung high in the air before plunging into the sea portside.

Within seconds, the ship was engulfed in flame and smoke. The lights went out and the ship started to settle by the stern.

On quickly ascertaining the seriousness of the ship’s condition, Dasher’s commanding officer, Commander Boswell, gave the order to abandon ship.

With the ship in darkness, disorientated congestion in allyways, queues to mount ladders, flames, smoke scalding steam and exploding ammunition, this was no simple procedure.

In the confusion, there was both much selfless heroism and tragic loss of life.

Within eight minutes, the ship had gone to the bottom. There was not enough time for all on board to escape.

At HMS Fortitude (Ardrossan), the response was instant.

A Royal Navy priority signal was sent – “All vessels put to sea immediately. Major rescue operation involving Royal Navy aircraft carrier HMS Dasher. Ship reported sinking”.

All available ships in Ardrossan harbour, and also ships from Lamlash, Brodick and Greenock, cast off and made their way to rescue Dasher’s survivors, hundreds of whom were in the water.

As the rescue flotilla drew near, there was a sudden whoosh and aviation fuel and diesel oil that had escaped from the ship’s ruptured tanks burst into searing flame that rapidly covered the surface of the sea.

Notwithstanding the cruel death to which so many in the water inevitably succumbed, the officer in command of the rescue operation gave the order: ‘Keep clear. We cannot afford to lose another ship.’

Lifeboats were lowered to take on board those who were clear of the flames, but astonishingly, the coaster Cragsman sailed straight into the flames and managed to lift 14 survivors, although many whose oil-covered hands slipped from the grasp of their frustrated rescuers could not be helped.

Then another coaster, Lithium, braved the flames and took on board 60. As the flames subsided, lifeboats and Navy ships joined the rescue operation.

As darkness fell, the rescue operation was called off and most of the Royal Navy ships were ordered to Ardrossan.

One by one, the returning ships discharged Dasher’s survivors, wrapped in blankets, most in bare feet, to be helped into a fleet of waiting ambulances or trailers.

The wounded, many badly burned, were aided by medical personnel; the dead, shrouded in the Union flag, were stretchered off the ships. Officers who did not require medical attention were taken to the Eglinton Hotel and ratings were billeted with local families.

Casualties were taken to the Royal Navy Sick Bay at South Crescent, Ardrossan, the first aid post in Saltcoats or Ballochmyle Hospital and the dead were taken to the morgue at Harbour Street, Ardrossan.

The navy made every effort to identify the deceased and 13 so identified and landed at Ardrossan were given full military honours and laid to rest at Ardrossan Cemetery, seven were buried at Greenock and others taken to familial locations.

Many remained unidentified and for some time bodies were washed up on the North Shore.

The government proclaimed secret the sinking of HMS Dasher and the huge loss of life.

The media were ordered to make no reference to the event. All survivors were ordered not to talk about the disaster and were further instructed not to leave Ardrossan until instructed otherwise.

For some days afterwards, as survivors passed the time of day with locals, they conveyed nothing of the events of that fateful day.

The families of the dead were led to believe that their loved one had simply been lost at sea. That they were never told the true circumstances, made the tragedy all the more heartbreaking.

In 1996, a small group of survivors and others linked with the disaster boarded the Arran ferry and after explaining to the ferry’s master, Captain Ian Riggs, their desire to cast roses as near as possible to the site of HMS Dasher’s sinking, the ship was stopped over the exact site for two minutes as a mark of respect.

Let us again remember those who lost their lives in the Dasher disaster.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel